Are constitutional reforms aimed at modern democracy or shifting the balance of power?

The reform agenda has to lead towards a modernized democratic system

I came across an interesting statistic today. In Constitution-making and liberal democracy: The role of citizens and representative elites by Gabriel Negretto, a chart shows the impact of constitutional replacement between 1900 and 2015 in terms of democratization, modernization, balance-of-power shift and political crisis. A new constitution in Denmark in 1953 led to a democratized system. A new constitution in Sweden in 1974 resulted in both democratization and modernization. A new constitution in Switzerland in 1999 led to modernization. A new constitution in Sri Lanka in 1972 resulted in only a shift in the balance of power. A new constitution in Venezuela in 1999 also resulted in merely a shift in the balance of power. In Trinidad, a new constitution in 1976 resulted in both a political crisis and more democratization. A new constitution in Bolivia in 2009 shifted the balance of power and caused a political crisis. In Colombia and Ecuador, new constitutions enacted in 1991 and 1998 respectively resulted in political crises. Nepal’s 2015 constitution is listed as having resulted in democratization.

As Bangladesh embarks on constitutional renewal, a key question is will the current reform process result in genuine democratization or simply shift the balance of power from the Awami League to BNP and Jamaat, or even worse, to a political crisis? The newly formed National Citizens Party (NCP) has called for a new constitution. Evidently, there is talk of constitutional replacement. But as I have argued in the past, the Bangladeshi way has been to preserve and amend the Constitution. Many basic features of the 1972 Constitution were radically altered in later years, including shifting the balance of power to a presidential system between 1975 and 1990; adding a state religion in 1988; and codifying the caretaker government system in 1996. But the basic structure in terms of democratic representation was preserved (albeit, at times suspended during martial law which the courts later declared to be illegal; parliament is also absent during the tenure of caretaker governments). I identify two important streams of constitutional interpretation in Bangladesh - one stream which emphasizes a return to the secularist text of the 1972 Constitution and considers the changes between 1975 and 1990 to be illegitimate; and another stream which pragmatically accepts the Constitution as it is and continues to support either conservative or progressive interpretations of constitutional law. The former stream is in the backfoot following the ouster of the Awami League. The latter stream represents reality as it is. The BNP, in keeping with President Zia’s approach, has expressed its intention to retain the existing constitutional order. The BNP and National Party have historically felt that their emphasis on Islamic nationalism can be expressed and articulated through the existing constitutional framework. Both these parties emerged during military dictatorships that sought to capitalize on the Islamic dimension of national identity in Bangladesh. The original 1972 Constitution had envisaged a secular democratic republic. Despite this clash between Islam and secularism in theory, most political parties support retaining the state religion, including the BNP, National Party and Awami League.

The NCP was at the forefront of demands to ban the Awami League, which the interim government caved into in May. But will Bangladesh also take the path of constitutional replacement as advocated by the NCP? The interim government has floated proposals to strengthen democratic procedures and freedoms in the constitution. Many of these proposals are being opposed by the BNP, which is traditionally a conservative party. Moreover, only political parties in the good books of the government are being consulted for reforms. The Jamaat has been a key beneficiary of the interim dispensation. The Jamaat’s ideology advocates an Islamic state based on Sharia law. There is no effort to consult the former ruling party and its coalition partners. This is made even more difficult by the complete lack of remorse from the current Awami League leadership regarding their authoritarian rule and the atrocities committed in the July Revolution. The interim government wants to prosecute and imprison the League’s leadership. The center-right National Party has also been left out of negotiations even though Chief Adviser Professor Dr. Muhammad Yunus established the Grameen Bank in 1983 during the military dictatorship of National Party founder H. M. Ershad.

Can we trust conservative and Islamist parties to bring about democratic reform? Both BNP and Jamaat have gained significant influence within the echelons of the interim government. Dr. Yunus appears to have taken power without foreseeing the pre-existing structural deficiencies which are prone to malign political influence, resulting in structural discrimination, illiberalism and authoritarianism. According to one estimate, 24 people have died in police custody under the Yunus-led interim government. Their bodies showed signs of torture. While the interim government was applauded for acceding to an international treaty on the prohibition of enforced disappearances, human rights groups expressed concern at a new domestic law which falls short of the standard of evidentiary proof that can be used to convict a force commander under whose command an enforced disappearance takes place. The UN Human Rights Office has also expressed concern at “legislation to allow the banning of political parties and organizations and all related activities”. The Chief Adviser was snubbed by the British Prime Minister during a visit to London where he received an award from King Charles. A meeting with the French President also did not happen.

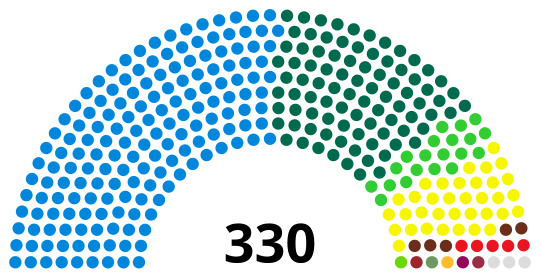

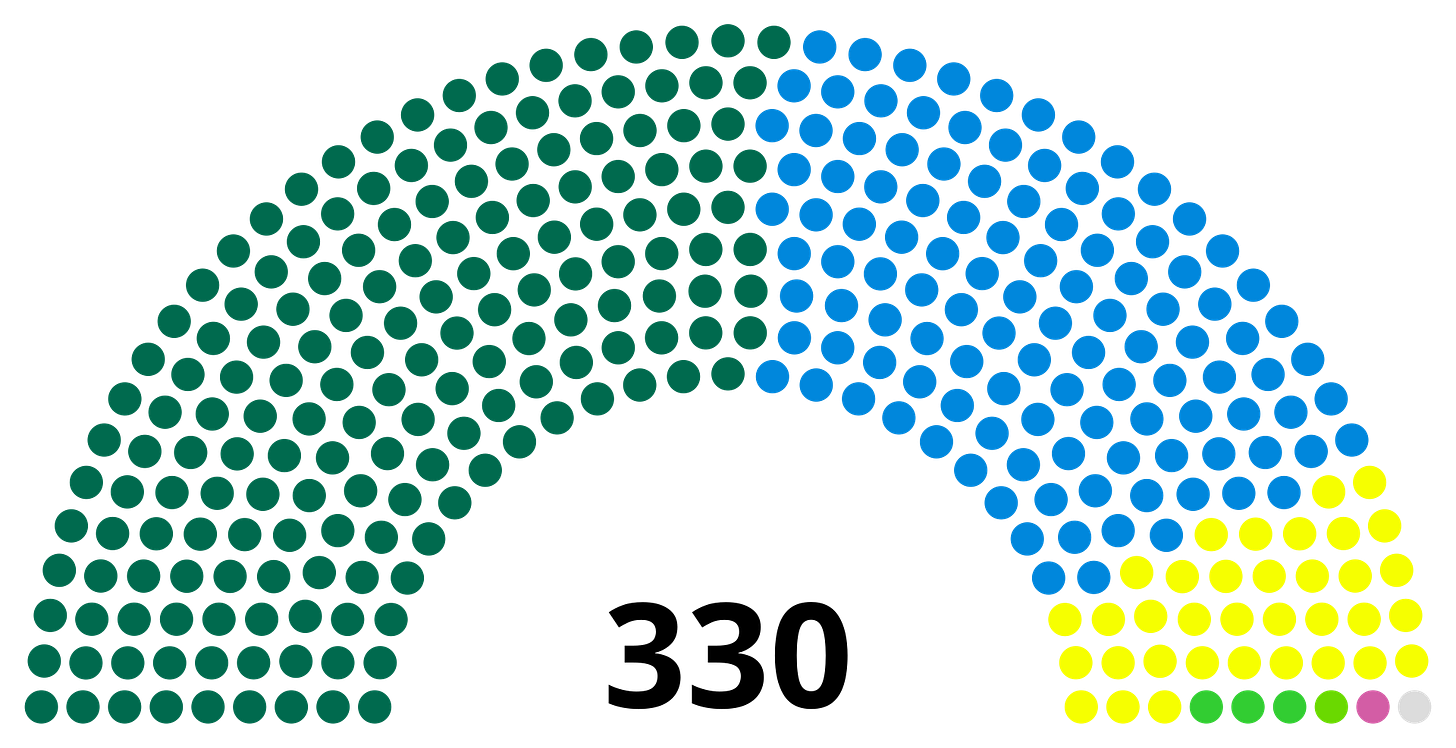

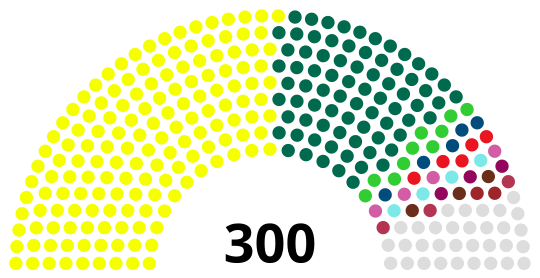

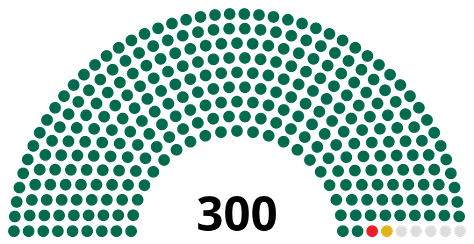

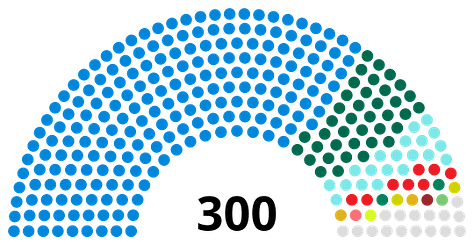

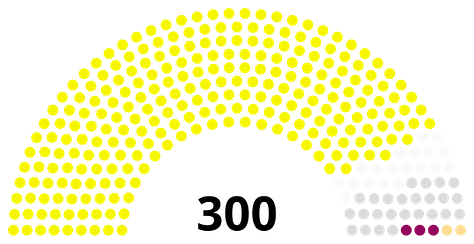

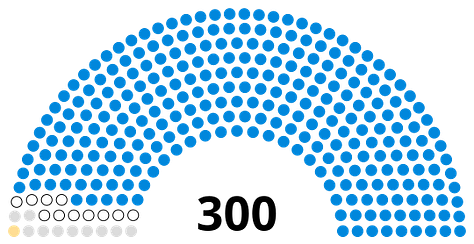

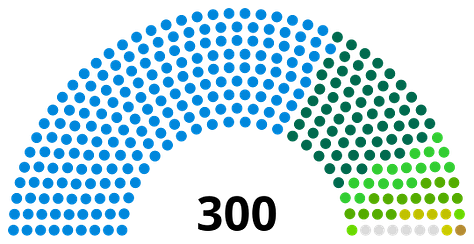

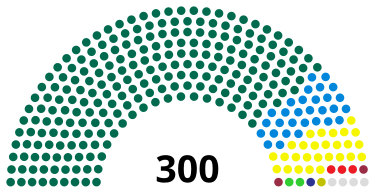

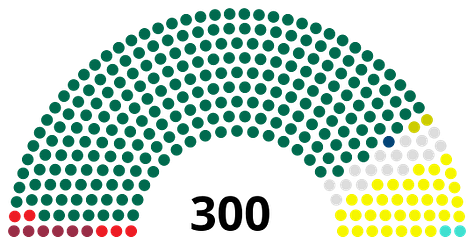

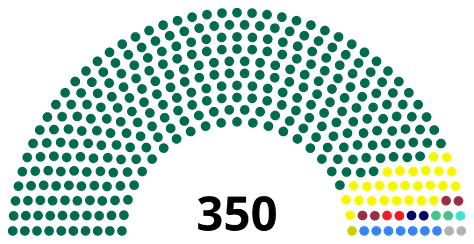

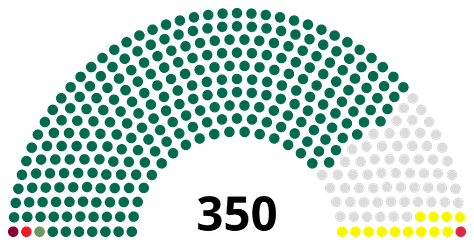

Given these shortcomings in the interim administration, will Bangladesh overcome these difficulties towards a modernized democratic system? The answer will lie in the result of the next election. Since 2001, every parliament has been dominated by a two thirds majority of the ruling party. This has led to calls for proportional representation. Despite holding a two thirds majority, the actual vote share of ruling parties has been significantly lower than the two-thirds threshold of 60%, and hovers around 30% to 40%. If Bangladesh retained the first past the post system, then how can the country avoid the one party dominance brought about by a two thirds majority? A robust, proportional and powerful multiparty parliament is the need of the day.

The third, fifth and seventh parliaments were the most multiparty and proportionally represented parliaments in Bangladesh’s history. These three parliaments have been the exception in a long line of single party dominated parliaments starting from 1972.

Democratization

Bangladesh needs to avoid merely shifting the balance of power. There needs to be genuine democratic expansion, including qualitatively better representation in parliament. Merely changing the guard in a corrupt, dynastic, mafia-style and entrenched two party system will hardly lead to democratization and modernization.

There is real fear that a system dominated by BNP, Jamaat and hardline Islamists may develop in the absence of strong checks and balances. Women’s rights, minority rights, social freedoms, an independent judiciary, a free press, and artistic and cultural freedoms may come under threat. The interim government plans to promulgate some checks and balances before the election. One example is the proposed disbanding of the controversial Rapid Action Battalion (RAB).

It is imperative that the next election produces a qualitatively better and proportionally represented parliament. Proposals for a bicameral legislature, stronger parliamentary committees and expanded voting freedom for MPs should be adopted.

Modernization

The next government should aim to enact major reforms in its first hours and first day in office. This would be taking a cue from Donald Trump’s signing of executive orders after he was sworn in as president. However, in Bangladesh’s case, the next government would have to implement significant liberal reforms without which the revolution of 2024 would be rendered meaningless. These reforms can include implementing the recommendations of the UN Fact Finding Report, including repealing colonial-era police laws, as well as outdated provisions of the penal code. Let’s remember that conservative and rightwing parties are triumphing on a platform to restore free speech and reinforce liberal freedoms from the tyranny of the left.