Indo-Bangladesh Relations during the Ershad Era

Indira Gandhi and Rajiv Gandhi worked pragmatically with H. M. Ershad

General Ershad’s coup and the installation of a new regime in Bangladesh was welcomed by the Indian government of Prime Minister Indira Gandhi. Ershad cited food shortages as one of the reasons for his coup. India agreed to supply 100,000 tons of wheat to Bangladesh. According to the account of former food minister Air Vice Marshal (retd.) A. G. Mahmud, a Bangladeshi delegation led by him met the Indian premier at her office in New Delhi. Clad in a white suit, the air vice marshal presented the Bangladeshi case for securing supplies of much needed wheat. This turned out to be a substantive area of cooperation between India and Bangladesh during the early period of the Ershad regime. The Indian foreign minister Narasimha Rao visited Bangladesh in May 1982 and promised to supply 100,000 tons of wheat.

General Ershad undertook an official visit to India in October 1982. He held talks with Prime Minister Indira Gandhi and discussed the whole gamut of bilateral relations, including trade, water sharing on transboundary rivers, maritime boundary disputes, land boundary disputes, and efforts for regional cooperation. They agreed to revive the Joint Economic Commission which remained dormant since the Mujib era. They also agreed to extend the 1977 Farakka treaty from the Zia era for two more lean seasons. Both sides affirmed their intent to amicably settle disputes concerning the land and maritime boundaries between India and Bangladesh. Ershad continued to pursue Zia’s foreign policy goals, including reaching out to India’s rivals and fostering a platform for India’s neighbors to build a regional community. Efforts to form a South Asian regional forum were being championed by Bangladesh’s foreign ministry. The two countries also emphasized the importance of the Joint Rivers Commission. A memorandum of understanding on sharing the waters of the Ganges was signed.

Ershad attended the Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting (CHOGM) and the summit of the Non-Aligned Movement in New Delhi in 1983. These multilateral gatherings provided a platform for India and Bangladesh to engage on the sidelines. The Ershad era saw a “maturing cooperative relationship” between India and Bangladesh in the context of the latter’s geopolitical situation following 1975. Differences, or even indifference, continued to persist more often than agreements. Bangladesh’s military rulers preserved covert strategic ties with China and Pakistan which were established during the Zia era. In India, debates were raging on whether to adopt a presidential system of government. Indira Gandhi reportedly considered leaving the premiership to become President of India. As late as 1984, sections of the Congress Party were lobbying for a switch to the presidential system. Sri Lanka had already adopted an executive presidency in 1978. Indira Gandhi’s assassination in 1984 laid to rest any plan for an executive Indian presidency. In Bangladesh, Ershad assumed the presidency in December 1983 under martial law. India’s engagement with the Ershad regime may have been premised on encouraging a return to democracy. But as business as usual continued under the Ershad regime, bilateral engagement gave way to multilateral and humanitarian diplomacy.

Domestic politics in India played a key factor in relations. In the Indian state of Assam, hostility grew towards the provincial Bengali population who were perceived as illegal settlers by the indigenous Assamese. Far-right Hindu nationalists accused Assamese Bengalis of being illegal migrants from Bangladesh. In bilateral meetings with Bangladesh, the Indian government began to raise the issue of illegal migration which Ershad stoutly denied as totally false. Evidence on the ground pointed to an effort to disenfranchise Assam’s Bengali-speaking population who lived in the state for generations. The movement by the All Assam Students Union reached its peak during Ershad’s martial law before losing steam after the Assam Accord in 1985. In West Bengal, a committee was formed to oppose the opening of the Tin Bigha Corridor, a narrow strip of land which allowed Bangladesh to access its enclave of Dahagram-Angarpota. Ershad traveled to the enclave by helicopter twice during his presidency. He became the first head of state to visit the ‘chitmahal’. These visits gave a sense of relief and belonging to the Bangladeshi citizens who inhabited the enclave. His helicopter was permitted by the Indian authorities to fly over Indian territory. Enclave politics was part of Ershad’s appeal to the voters of North Bengal. Ershad himself hailed from the Rangpur region of North Bengal and his father’s family was historically settled in the princely state of Cooch Behar. Enclaves on the Indo-Bangladesh borderland were part of the legacy of Cooch Behar’s realm.

A devastating cyclone hit the Chittagong coast in 1985. The island of Urir Char was one of the worst hit areas. Indian Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi flew to Bangladesh to see the devastation first hand. After arriving in Dhaka, he was flown by helicopter to Urir Char near the coastline of the port city of Chittagong. He flew back to Dhaka by the end of the day and returned to India. When a journalist asked him in Dhaka about his impression of Bangladesh, the Indian premier replied with a polite smile that he had been to only Urir Char and thus had no comment to offer. The Sri Lankan President J. R. Jayawardene also visited the devastated island in the Bay of Bengal.

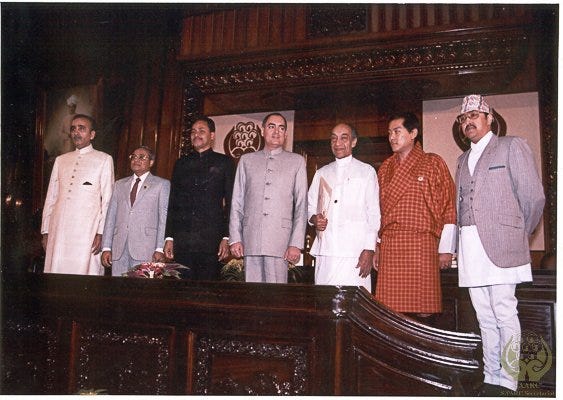

Ershad met Rajiv Gandhi on the sidelines of the Commonwealth summit in Bahamas in October 1985. In December 1985, Rajiv Gandhi visited Dhaka again for the founding summit of the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC). He was joined by the leaders of Bhutan, Sri Lanka, Nepal, Pakistan and the Maldives. Ershad attended the second SAARC summit in the Indian city of Bangalore in 1986.

During the devastating flood in 1988, Bangladesh delayed the acceptance of Indian aid which was offered to support relief operations. Bureaucrats in Dhaka felt the Indian offer was unnecessary in view of Bangladesh’s own fleet of relief equipment. The offer was eventually accepted. Ershad traveled to Delhi to thank Rajiv Gandhi. The two men held talks for a marathon six hours at Hyderabad House. Bangladesh pressed India for stronger flood prevention measures. As the downstream country, Bangladesh was vulnerable to floodgates on the upper riparian side in India where several dams and barrages were built. Bangladesh argued for third party mediation to resolve water disputes. India remained firm on negotiating within a bilateral framework. Ershad was able to convince Gandhi to form a task force for flood management. This agreement was noted by a joint communique issued at the end of their talks.

When Bangladesh’s parliament declared Islam as the state religion as part of the Eighth Amendment in 1988, the Indian prime minister described the move as an internal affair of Bangladesh. Indeed, H. M. Ershad and Rajiv Gandhi enjoyed a certain positive chemistry which translated into cordial relations. Despite Indian concerns over Bangladesh’s ties with Pakistan and China, the chemistry between Ershad and Gandhi steered the Indo-Bangladesh relationship towards a momentum of engagement and dialogue, despite significant differences. This was reflective of the maturing cooperative relationship between Delhi and Dhaka during the Ershad years.

In 1988, Ershad appointed a British-trained barrister as his prime minister. Moudud Ahmed was the postmaster general of the Bangladeshi government-in-exile during the Liberation War in 1971. The government-in-exile was based in Calcutta. Ershad’s constructive engagement with India proved to be short-lived. In 1989, the Congress Party led by Rajiv Gandhi lost the Indian general election to the Janata Dal. Ershad moved to replace his pro-Western premier with a pro-Chinese leftwinger, Kazi Zafar Ahmed. Ershad himself retained power for only a year afterwards. He resigned amid a mass uprising against his regime in the winter of 1990.

Footnotes

Shahnawaz A. Mantoo, INDIA-BANGLADESH RELATIONSHIP (1975-1990). 3 Journal of South Asian Studies 3 (2015) 341-349

Md. Habibullah and Emran Hossain, Bangladesh-India Diplomatic Relations (1975-1996): Transitions, Bilateral Disputes, and Legacies. Global Journals (2020)

A Bangladeshi remembers Rajiv Gandhi by Syed Badrul Ahsan (Open Magazine, 29 May 2021)

Gandhi and Sri Lanka Leader Plan A Joint Bangladesh Visit (The New York Times, 1 June 1985)

Note(s): A transit protocol signed in 1972 was renewed in 1984 and extended in 1986 on a quarterly basis until October 1989.