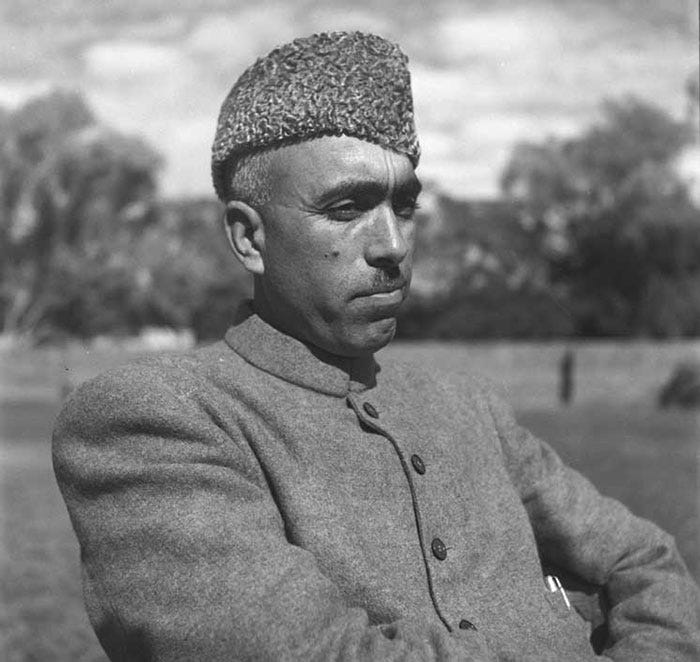

In October 1951, an election was held for a Constituent Assembly in Indian-administered Jammu and Kashmir. All 75 seats were gobbled up by the National Conference, a party which enjoyed the backing of New Delhi and Indian intelligence agencies. Its leader Sheikh Abdullah was influenced by Nehruvian socialism, but remained ambiguous about full integration with India and wanted autonomy for Muslim-majority Kashmir. Ian Stephens, an erstwhile editor of the Calcutta Statesman, remarked that Abdullah’s regime was backed up by “Indian bayonets, which meant mainly Hindu bayonets”. In the election, the National Conference won seats unopposed except in three constituencies. The opposition Praja Parishad from the Hindu-majority Jammu region had boycotted the election.

Stephens saw Abdullah as “a man of pluck and enlightenment, standing for principles good in their way; a victim, like so many of us, of the unique scope and speed and confusion of the changes in 1947, and now holding a perhaps uniquely lonely and perplexing post”. On the National Conference’s governance of Kashmir, Stephens said “in many ways it was a good regime: energetic, full of ideas, staunchly non-communal, very go-ahead in agrarian reform”. But Stephens concluded that “to the eye of history, it might prove to be an unnatural one”. Sheikh Abdullah was later imprisoned by Nehru as part of Kashmir’s full integration with India. The National Conference reached a settlement with the Indian state after the Liberation War of Bangladesh.

In the 1950s, India’s first prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru developed an affinity for secular Arab nationalist leaders. Egyptian leader Gamal Abdel Nasser supported Nehru’s vision for a non-aligned movement. India also developed strong ties with the Ba’athist regimes of Syria and Iraq, as well as the Communists in Afghanistan during the Soviet occupation. India’s most important political ally in Muslim South Asia, the Awami League in Bangladesh, also adopted authoritarian socialist policies. The League was also led by a sheikh, the Bengali politician Sheikh Mujibur Rahman. In 1975, Sheikh Mujib transformed Bangladesh into a one party socialist state under the banner of BAKSAL and banned all political parties. The one party state proved to be short-lived as Mujib was assassinated that year and BAKSAL was formally discarded. In 2009, the Awami League rode to power on the back of hopes for liberal democracy. By 2014, the national election was boycotted by the opposition BNP and the Awami League won many seats unopposed. It would appear that the Awami League’s Indian allies may have used the Kashmir playbook to lend advice to Sheikh Hasina. The lesson here is that Bangladesh must safeguard its sovereignty, internal cohesion and national independence from the mischief of competing powers in South Asia.

The National Conference today is led by the articulate grandson of Sheikh Abdullah. It has evidently transformed into a social democratic party. Can the same be said for the Awami League? Can the Awami League learn to co-exist with other political groups in Bangladesh, particularly political parties formed during military dictatorships? The military usually feels obliged to intervene because of the Awami League’s naked subservience to corrupt and malign influences from across the border.

Footnotes

India After Gandhi by Ramachandra Guha