Third International Criminal Law Conference

Bangladesh's call for an International Criminal Court in 1974

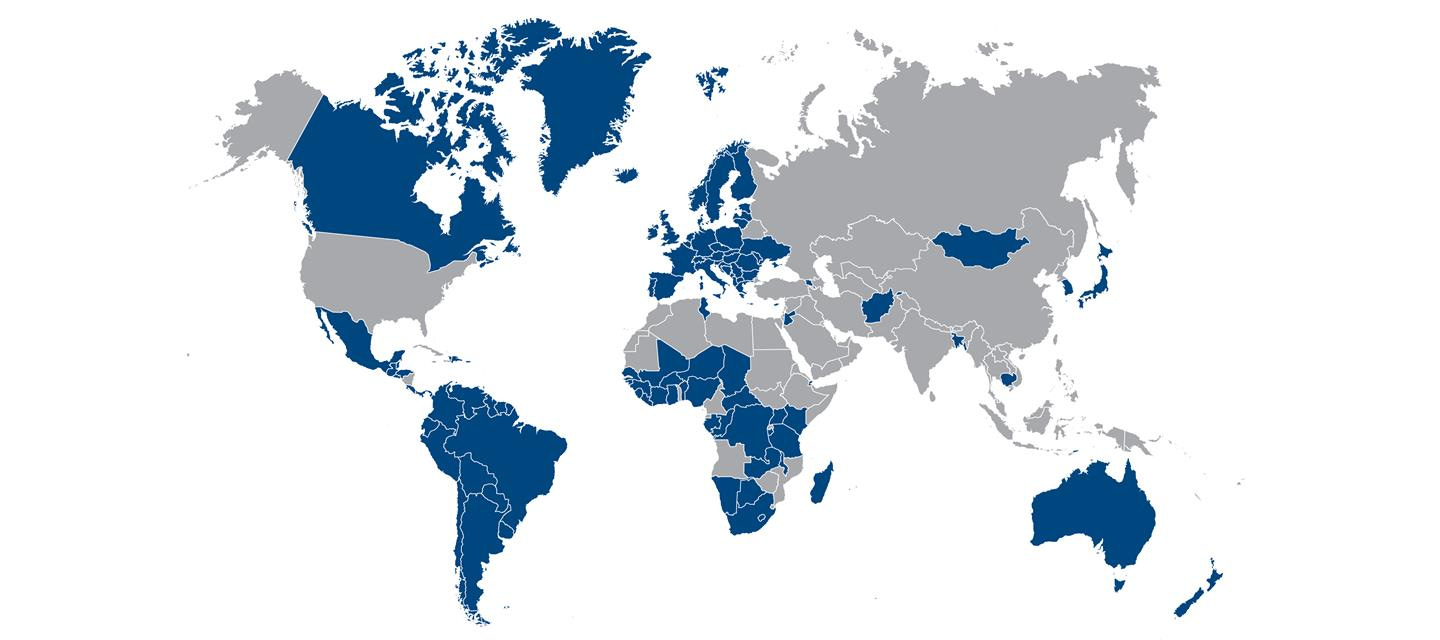

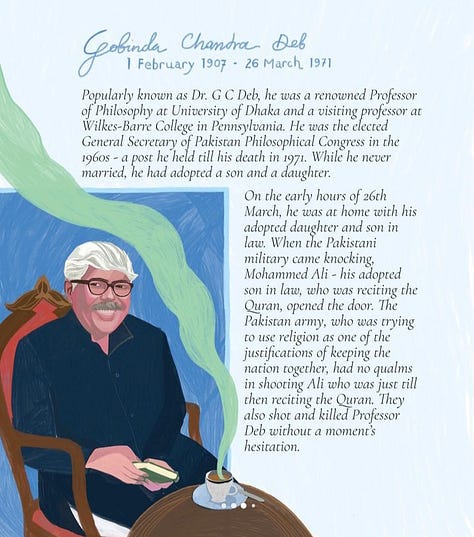

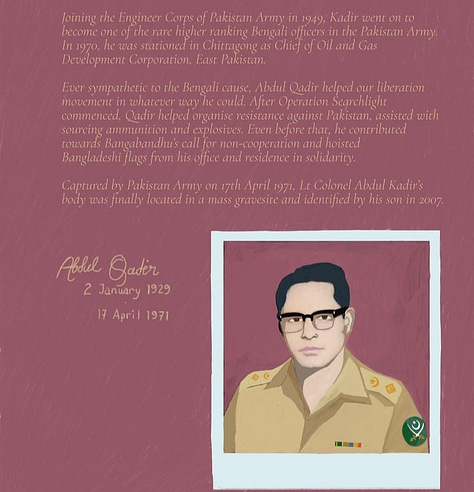

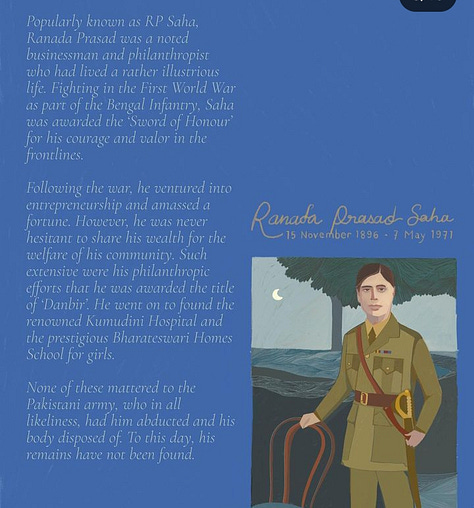

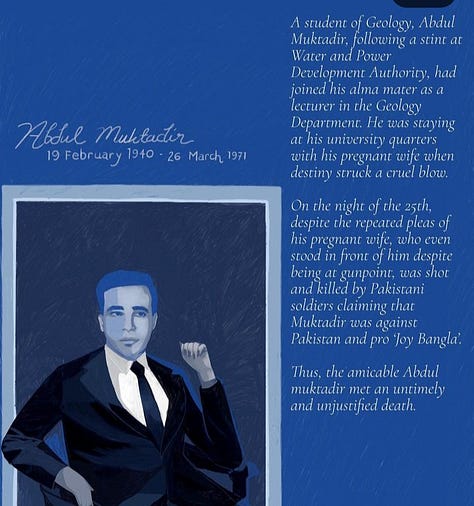

Some of the victims of Operation Searchlight in 1971. [Illustrations by DHAKAYEAH]

The International Criminal Court, which was established in 2002, was the product of an international legal movement that gained pace after 1971. In January 1972, an article in the American Journal of International Law called for the creation of a permanent international court to prosecute those accused of the most egregious crimes under international law, including genocide, war crimes, and crimes against humanity. The celebrated Nuremberg prosecutor Benjamin B. Ferencz and academic Robert K. Woetzel were at the forefront of these efforts.

Ben Ferencz (left) and Robert K. Woetzel (right)

This coincided with calls for accountability for the genocide in Bangladesh in 1971. In the early 1970s, the first government of Bangladesh found itself in delicate negotiations regarding the fate of 195 Pakistani Prisoners of War (PoWs) being held in India. These 195 PoWs formed the top echelons of the Pakistan Eastern Command and the martial law regime during the Liberation War in 1971.

There was considerable international pressure to release these PoWs. Pakistan even filed a lawsuit at the International Court of Justice demanding the return of these PoWs. Pakistan later withdrew the case. Negotiations between India, Pakistan and Bangladesh resulted in the Tripartite Agreement, in which Bangladesh agreed to the transfer of these 195 PoWs to Pakistan in the absence of an international mechanism to prosecute war criminals. At the same time, Bangladesh declared that “the excesses and manifold crimes committed by these prisoners of war constituted, according to the relevant provisions of the U.N. General Assembly Resolutions and International Law, war crimes, crimes against humanity and genocide, and that there was universal consensus that persons charged with such crimes as the 195 Pakistani prisoners of war should be held to account and subjected to the due process of law”. Pakistan’s response was that it would form an internal inquiry. The results of that inquiry, known as the Hamoodur Rahman Commission report, were never made public. The inquiry was also an attempt at downplaying the scale of the massacres which occurred. Pakistan backtracked on its pledge to carry out domestic prosecutions.

Report by Anthony Mascarenhas in The Sunday Times on the genocide in Bangladesh.

In December 1974, the Bangladesh Institute of Law and International Affairs (BILIA) organized the Third International Criminal Law Conference in Dhaka. Bangladesh was, in effect, giving its full support to the movement for the establishment of a permanent international criminal court. Distinguished professors of international law from around the world gathered in Dhaka to attend the conference.

Foreign Minister Kamal Hossain delivered the opening remarks during the inauguration of the conference. The following contains his speech:

Speech by Foreign Minister Dr. Kamal Hossain at the opening of the Third International Criminal Law Conference on 28 December 1974:

The holding of the Third International Criminal Law Conference in Bangladesh has a special significance. For barely three years have passed since Bangladesh was the scene of the commission of some of the gravest of international crimes on a scale which shocked the conscience of humanity. Indeed many of the eminent jurists here present, and those associated with the movement for the establishment of an international criminal court have cognizance of the atrocities committed here and actively considered the question of the criminal liability of the persons responsible for the commission of those crimes. It was this interest that had led to an invitation being extended to me and our Special Prosecutors to attend the Second International Criminal Law Conference at Bellagio, Italy, in 1972. I, therefore, deem it a great honour to inaugurate the Third International Criminal Law Conference in the capital city of Bangladesh. I would like to thank the Foundation for the Establishment of an International Criminal Court, and its President, Professor Robert K Woetzel, for the initiative taken by them to hold this Conference in Dacca. I would also like to welcome the distinguished jurists who have travelled long distances to be here in this Conference.

The great task with which this Conference is concerned, as were the two earlier International Criminal Law Conferences, is that of devising an international machinery for the prosecution and punishment of those responsible for the commission of international crimes. Mankind has recoiled with horror at the commission of crimes which strike at the very root of human civilization. Such crimes include genocide, atrocities, which are appropriately described as “crimes against humanity,” crimes against peace, and slavery. The world has not forgotten the horrors that were perpetrated by the fascist governments in the Second World War. It cannot forget the massacres, the extermination camps, the cruelty and the human degradation which had been perpetrated on an unprecedented scale. Our own recent experience has shown that the evil tendencies which lead to such crimes can surface anywhere at any time.

Since the Second World War, therefore, there has been increasing awareness of the need for establishing machinery for the prosecution and punishment of individuals responsible for the commission of such crimes. The United Nations from its very inception took up this matter. Initiatives taken in that forum produced the Genocide Convention, the approval of the Nuremberg principles, and the preparation of a draft Code of Offences against the Peace and Security of Mankind and a draft statute for an international criminal court. The existence, however, of an international order in which the concepts of state sovereignty and domestic jurisdiction continued to predominate, was not conducive to generate the consensus necessary to create an international machinery for the punishment of international crimes. Thus within the United Nations, the question of establishment of an international criminal court was allowed to be linked with the problem of defining “aggression”, and was thus shelved for two decades. It is indeed a happy augury that this Conference is being held soon after the United Nations General Assembly has at last approved a definition of “aggression”. It may now be hoped that the matter of the establishment of an international criminal court may be re-activated in the United Nations.

There is no doubt that an international criminal court which enjoys universal respect remains the ideal. A successful strategy aimed at establishing such an institution must, however, take into account the considerations which continue to inhibit states from immediately supporting the establishment of a full-fledged international criminal court. A Conference such as this can and should hold out the ideal which should be aimed at and aspired for. At the same time, an awareness of current international realities would favour an evolutionary approach, which would initially aim at creating a nucleas, which would grow organically, and ultimately develop into an international criminal court enjoying universal jurisdiction. The earlier conferences have in fact adopted this approach, as would be evident from the two draft Conventions which represent the fruit of their labour. The draft Convention on International Crimes contains an enumeration of international crimes. Flexibility is provided by an open-ended enumeration, which would permit states to join the system in respect of some, if not all, of the enumerated crimes, which may come to be recognized as international crimes. Thus ‘apartheid’ and grave breaches of humanitarian rules governing all armed conflicts can today claim to be included in this list. The other Convention is in the form of a draft statute for an international criminal court. This would enable state parties to the Convention immediately to establish a system which would operate among themselves, while they concerted their efforts to obtain adherence of other states. Within the framework of this Convention, it is contemplated that until a full-fledged international criminal court is established, national machinery could be resorted to for prosecution and punishment of offenders. Indeed, the absence of international machinery had led Bangladesh to establish its own national machinery for this purpose. Ultimately, as you know, the appeals for mercy in respect of those who were to be tried by this machinery, resulted in a grant of clemency, which was clearly premised on an admission of guilt and a condemnation of the atrocities committed.

The task before this Conference is a challenging one. It is that of contributing towards the development of an effective framework for the prosecution and punishment of international crimes. This involves a definition of international crimes, an enumeration of the principles of criminal liability applicable to them, and the establishment of institutions for investigation, prosecution, trial and punishment of such crimes. Having been myself associated with this work, both within the country and in the Second International Criminal Law Conference and the World Peace Through Law Conference in Abidjan, I have no doubt that this is an urgent and important task. I therefore, wish success to the participants in their deliberations, and conclude with the hope that they may look back upon their deliberations at Dacca as having been fruitful and as having taken them a step further in their quest for a system which would ensure that those responsible for committing international crimes are brought to justice.

Legacy

Alongside supporting the movement for a global penal court, Bangladesh enacted domestic legislation for the prosecution of war crimes. 11,000 local collaborators of the Pakistani army were detained under the Collaborators Tribunal Order 1972. The first amendment to the Constitution of Bangladesh in 1973 paved the way for the enactment of the International Crimes (Tribunals) Act. The provisions of this law allowed a dual-tier system of trials, with international and local judges.

The movement for a global penal court crystallized in 2002, when the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court was adopted. Bangladesh ratified the Rome Statute on 23 March 2010. As of 26 March 2024, Bangladesh is the only country in South Asia which is a state party of the Rome Statute.

Today, Bangladesh has to ponder on developing a comprehensive law on crimes under international law. Many countries already have a Code of Crimes against International Law, including Germany, Spain, France and Argentina. Developing such a law will strengthen Bangladesh’s legal credentials when it comes to the discourse on genocide.

State parties of the ICC as of 26 March 2024.

Footnotes

Address by Dr. Kamal Hossain, Foreign Minister of Bangladesh, at the opening of the Third International Criminal Law Conference hosted by The Bangladesh Institute of Law and International Affairs (BILIA) at the Intercontinental Hotel in Dacca, Bangladesh on December 28, 1974.

Bangladesh can heal from the 1971 war by Pritilata Devi and Ansar Ahmed Ullah (Whiteboard, 17 March 2024)